The Highway’s Jammed with Broken Heroes: Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born to Run’ at 50

The Boss worked on his third album like it was the last one he’d ever make. It paid off.

by Tony Gervino

It seems almost inconceivable that just over a half-century ago, a 25-year-old Bruce Springsteen sat down to write the songs that would become his third album, Born to Run, knowing that he was on borrowed time with his label, Columbia Records.

In fairness, Columbia thought they’d signed the next Bob Dylan, and planned to market him that way. The only problem was, had they spent time watching his live performances, they’d have known they actually signed Van Morrison, backed by Booker T.’s band, the M.G.’s. And that disconnect was no more vivid than on his first two ramshackle albums, both of which were a far cry from the quiet, captivating demo tapes he recorded at the behest of legendary record executive, John Hammond.

Despite glowing reviews, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. (1973) and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle (1973) were commercial duds. And even someone relatively new to the industry like Springsteen realized that one more album without a legitimate hit and he would likely wind up like a character in one of his songs. And not the guy making love in the dirt in “Spirit in the Night.”

Columbia underwent management changes in ’74, and the new bosses wanted a return on their investment. Some were understandably dubious, but they’d come this far, and so they gave him some money and studio time and told him not to return without a potential hit record. No pressure.

No one, not even Asbury Park’s boardwalk psychic Madam Marie, could have predicted what was to come next.

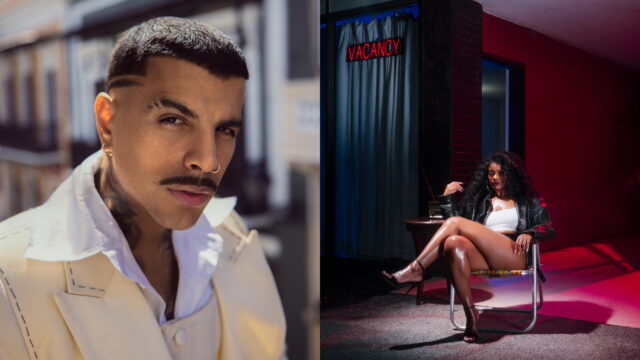

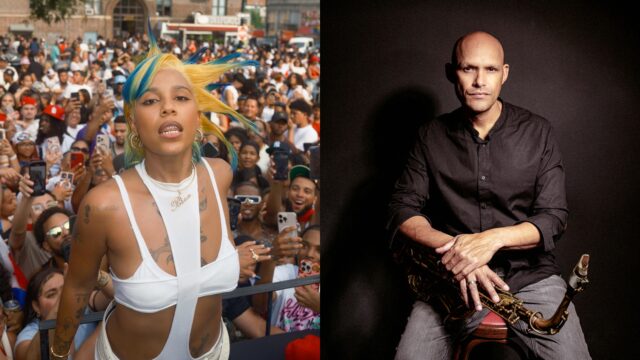

The song Springsteen delivered was “Born to Run,” which was sonically enormous and a creative leap from his prior releases in every way. It was literally a different species than the rest of his catalog — with dozens of layered guitar tracks, a booming saxophone solo, a glockenspiel, sweeping keyboards from outgoing band member David Sancious and a furious rhythm propelled by the singular drumming of legendary studio and jazz musician Ernest “Boom” Carter. “Born to Run” opens with a military drumroll, and builds and releases several times, while Springsteen delivers some of the most iconic rock lyrics of all time.

Baby this town rips the bones from your back / It’s a death trap / It’s a suicide rap / We gotta get out while were young / ’Cause tramps like us, baby we were born to run

The song is dramatic and fierce, and its urgency barrels out of the speakers like a hurricane repeatedly making landfall. In Springteen’s six-decade career, during which he’s won numerous Grammys, a Tony and an Academy Award, “Born to Run” is his signature creative achievement.

If the label was looking for proof of life, this was an undeniable sign. So they sent him back to the studio for what they’d hoped (in vain) would be an expedited recording process. News flash: it wasn’t, and the sessions ended with the album practically being wrenched from Springsteen’s hands.

That was 50 years ago and the rest, as they say, is history.

Springsteen’s writing on the album Born to Run is simply remarkable, full of sweeping detail and nuance, while avoiding his prior tendency to use a paragraph when a word would suffice. It’s a truly cinematic journey that begins quietly on “Thunder Road,” with a plaintive piano and harmonica, and lyrics that unfold like the opening scene of a John Ford film.

The screen door slams / Mary’s dress sways / Like a vision, she dances across the porch as the radio plays / Roy Orbison singing for the lonely / Hey, that’s me and I want you only / Don’t turn me home again / I just can’t face myself alone again

As the album continues, separate but thematically linked songs — “Tenth Avenue Freeze-out,” “Night,” “Backstreets,” “She’s the One” — unfurl, each one brimming with restless energy, an early rock and roll romanticism, and lyrical bravado, all stitched up with a ’70s post-Vietnam disillusionment and longing for a return to normalcy.

Born to Run is an eight-act play about missed connections, whether by design or misfortune. It’s the narrator trying to coax Mary into his car on “Thunder Road” or pleading with Wendy to let him in on “Born to Run.” There was no happily-ever-after implied on any of the tracks — the narrator clearly didn’t end up with Terry on “Backstreets” and the less we say about the Magic Rat’s fate on “Jungleland,” the better.

Yet, in a strange way, the album’s also a bit hopeful. No one is throwing in the towel and they’re still down for whatever, in spite of being worn down by life. The songs’ characters are ready to fight for what’s theirs, and are willing to sacrifice to try to get somewhere, even if they know they won’t ultimately succeed.

Musically, Born to Run is precise and measured, which, again, was a sharp turn from what Springsteen had previously released. It’s a guitar-heavy record, occasionally split by Clarence Clemons’ signature tenor sax runs and Roy Bittan’s expressive piano. Drummer Max Weinberg performed on every track other than the title one and his ability to bring structure to the songs was entirely different from the band’s prior drummer, Vini Lopez, who was appropriately nicknamed “Mad Dog.” Lopez was the human equivalent of Animal from the Muppets, which was fine for the early ’70s live shows, but a nightmare to try to musically corral.

The album closes with a nine-and-a-half-minute mini-opera, “Jungleland,” during which the main character’s “own dream guns him down.” The song eventually ends up returning to the most impactful instrument on the entire album: Springsteen’s voice, which embodies longing, regret and fleeting hope before devolving into an anguished howl. It’s the sound of desperation — for the characters that inhabit Born to Run who never seemed to make it out of the world Springsteen had built for them. But more than that, it’s the sound of an artist, finally — and somewhat painfully — growing into his own mythology.

And not a moment too soon.