Dan Wilson Interview: Inside Songcraft, From Adele to Nas

At the helm of Semisonic, he gave us “Closing Time.” With Adele, he co-wrote “Someone Like You.” Alongside the Chicks, he crafted “Not Ready to Make Nice.” In this extensive interview with Dan Wilson — whose new solo EP is Dancing on the Moon — the Grammy-winning songwriter shares his hard-earned insights on the subject of words and music.

by Ryan Reed

Most pro songwriters build careers out of niches — after all, formulas sell. But the beauty of Dan Wilson’s catalog is how bizarre, even disorienting, it looks on paper.

The Minnesota native, now 61, broke out as the singer and guitarist for alt-rockers Semisonic, who scored a hit with the 1998 quiet-loud singalong “Closing Time.” But after the band’s first breakup, he stumbled into a career as one of popular music’s most versatile, in-demand craftsmen, racking up credits with pop stars (P!nk, Taylor Swift), major rock bands (Weezer, My Morning Jacket), country artists (LeAnn Rimes, Dierks Bentley), electronic acts (Phantogram), even rappers (Nas).

Wilson could easily have taken a more predictable, and ultimately less satisfying, path. Under producer Rick Rubin, he wrote “Not Ready to Make Nice” with the Chicks, and the song went on to win three Grammys, among them Record and Song of the Year, in 2007. Again at the invitation of Rubin, who produced Wilson’s 2007 solo debut, Free Life, he co-wrote three songs on Adele’s 2011 blockbuster, 21 — including the show-stopping piano ballad “Someone Like You,” which won the inaugural Grammy for Best Pop Solo Performance. After that explosive success, he suddenly found himself bombarded with major, and sometimes majorly ill-fitting, offers. Many seemed like smart career moves, but they left him feeling hollow.

“I was talking with a friend of mine, who’d won an Oscar for a documentary film he made, about me winning the Grammy with Adele,” Wilson says. “He said, ‘I got a lot of offers to do work that I would be better off not doing.’ And that was really interesting to me. One of the things about the post-‘Someone Like You’ era was that I got a lot of offers to do very poppy, TV-star-making-a-record type of work — things that were driven by the business rather than interest or curiosity. I thought, ‘It would be dumb for me not to take these opportunities.’ But every time it was always a failure — it never went well. I had to get my compass back.”

So he did, choosing to work with artists who push him musically; his résumé proves he’s willing to collaborate with anyone who can teach him something about the craft. (He shares those lessons on social media through his meditative, often philosophical series “Words + Music in 6 Seconds.” Sample tweet: “Take care of the sounds of the words and the vowels, and the meaning might well take care of itself.”)

“I love the idea that some of the things I say online sound like a pep talk,” he says of Words + Music. “I’m not sure if I’m much of a coach, but sometimes [it’s me] trying to give someone a reason to feel encouraged or a little more confident where they’re at.”

And he’s still finding time to explore for his own projects: He reunited with Semisonic for the 2020 EP You’re Not Alone, and his latest solo EP, Dancing on the Moon, dropped Sept. 28. Wilson took a break from a busy day of writing — “I can’t tell whether this song is supposed to be really quiet or really loud,” he says of one in-progress track — to chat about his winding career, the art of staying flexible and the importance of artists having stories.

In interviews, you’ve talked about a pivotal early co-writing session with Carole King, a major influence on you. You’ve described how, if you didn’t respond to one of her ideas, she would quickly fire off a new one. It reminded me of improv comedy — the “yes and” principle.

I love that “yes and” improv principle, and I learned about it after I’d had this writing session with Carole. She would propose an alternate idea when I said, “Hmm, I’m not sure about that.” She’d say, “How about this?” It’s like she could just turn on the faucet and think of another idea. She never advocated or argued for the previous idea — she just blasted out a new one. The reason it differed a little bit from “yes and” in the experience I had is that it sprang from me being hesitant about some aspect of a song we were working on. I wasn’t really doing “yes and” — she was doing most of it. [laughs] But it really did influence the way I thought about it subsequently.

I imagine that was a big change coming from a band background, where egos are often more at stake.

Band songwriting and band life, in my experience, was not like comedic improv. It was more like, “No, that idea sucks,” or “I would never play that guitar part” — a jousting of egos and negotiation and refusal. So going from that into that first session with Carole King was so [impactful], because she was both yielding and powerful at the same time. She yielded to my question marks very actively and just said, “What about this amazing idea? Boom.”

You clearly love so much music, including stuff people probably wouldn’t expect, given your output. Your recent tweets include praise for Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Shining Star,” Monolord’s “The Weary” and Yes’ Tales From Topographic Oceans. That also ties nicely into another bit of wisdom you shared: “Your music doesn’t have to include everything that you like. I love to listen to Mastodon but nobody needs to hear me make those sounds.”

I have a friend named Craig who told me that a song of mine was a really good, dark, scary and ominous song, but he also said, “Dan, we don’t need that from you.” I was kind of blown away because, first of all, it’s kind of an arrogant thing to say, but in a great way — like he was speaking for the whole world at that moment. He was a delegate: “We in the world don’t need that from you.” [laughs] It was very liberating. One part was like, “You don’t need to impress us by being able to do many things.” And the second thing: “Go ahead and do what sounds or feels best or most authentic when you do it. Don’t worry that it’s not mean enough or hard enough or savvy enough. Go do the thing that most naturally comes from you.”

Do you often come up with stuff that people wouldn’t expect from you, like metal riffs, and think, “No, I don’t have to do that”? Are you having that dialogue with yourself?

I am! If I’m playing guitar alone in my music space and recording myself, sometimes I’m playing something really loud and nasty-sounding. And in a way I’ll know on some level that I’m probably not the right singer for this, if it even ever has a singer. But at the same time, I’m enjoying the learning — I’ll happen upon a tone I’ve heard on someone’s record and go, “Ohh, this is how they got that tone.” I’m exploring on a purely curiosity-driven level.

Then there’s another thing: For better or worse, part of the thing about sharing music with other people is that you have to help them understand why they’re supposed to like it. That’s why everybody needs a backstory about the artist — it helps you understand why you’re supposed to sympathize with them or idolize them or be amazed at their audaciousness. You need to know what they are, not just [listen to it] completely in an artistic vacuum.

Sometimes you have to choose pieces of music based on what it does to the story of the artist that we have in our minds. I love Aphex Twin. I can imagine a whole bunch of different Aphex Twin recordings that would make no sense to me — like, “Why is Aphex Twin doing this?” Because I have an impression of who that artist is or what they’re likely to do. If they can bring me along and put out an acoustic, busking folk-song record that makes sense to me with that story, I think that could be amazing. But I don’t want tender, acoustic-guitar love songs to be sprinkled in with the rest, with no explanation whatsoever. It’s not really a crime that we have a story about the artist in our minds when we hear that artist’s next song — it actually enriches the experience.

That’s a good point. It would be jarring for fans if you recorded 10 folk albums and then suddenly made a disco song.

It can be done right. The new Beyoncé record is not a complete change of direction, but it’s an embracing of certain aspects of the culture that she wants to embrace right now. But it is a little bit David Bowie-esque in how different it is from a couple records ago. But she did it! She brought us along. We understand in a way why this character that we look up to has created this new kind of palette of colors for their work. And that’s exciting.

As a listener, do you try to absorb as many styles of music as possible, even if you’re not applying it to your own work?

I just naturally gravitate to great things in lots of different styles. It reminds me of conversations I’ve had with Rick Rubin about this. He’s very eclectic too. He didn’t say this explicitly, but it kind of coalesced from some conversations I had with him. He would almost think of music, when it’s at its greatest, as making him laugh — not because it’s comical, but because it’s almost funny, on some level, how great a piece of music can be. If a piece of death metal is so amazing that you just start laughing, that’s not much different from hearing a Mozart sonata that’s so delightful and hilarious that you just start laughing. I was listening to Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Saturday Nite” recently, and it just made me laugh, the way the groove worked and how the bass was conversing with the vocal. It was almost like this really funny, brilliant improv comedy as much as anything. It’s composition as much as Mozart — or Bach or something like that. That feeling of something being funny or delightful kind of transcends the stylistic boundaries.

I was with two friends of mine when I was a teenager, and we were at a B.B. King concert. There was one particular moment when we were caught up in the euphoria of the music, and he played one note — one springy, vibrato-y note — to begin the solo. Me and my two friends all broke out in laughter. We couldn’t help it. I realized I wasn’t the only one who would laugh when a piece of music is awesome. I also realized, “OK, these guys are my soulmates.” [laughs]

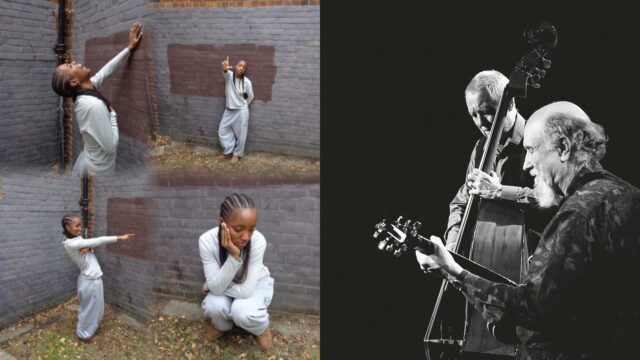

Credit: Michael Caulfield/WireImage/Getty Images.

Sonically, your new EP sounds modern and contemporary. It sounds very of its time — in a good way.

I agree with you. It’s like Dan the busker meets Dan the guitar pedal and computer experimenter. I think it’s partly more modern because it’s way more sonically experimental, and I’m putting a lot more effort and joy into creating the sonic landscapes. Some of the guitar tools I use a lot are some of the ones that end up getting used for hip-hop sample elements. It’s not me trying to sound stylistically that different — it’s just me turning up the wild guitar sound.

In your “Words + Music in 6 Seconds” series, you talked about the importance of being generous with songwriting credit. Can you think of an example where spreading the credit around ended up being very helpful for you?

There was one experience I had with Jason Mraz, with whom I’ve written a bunch of songs. He and I had a long hang while he was working on [Mraz’s 2008 album] We Sing. We Dance. We Steal Things. We talked about a bunch of the songs, and I gave him some pretty useful thoughts. There was one song where I thought of a simple change that was good but not earth-shattering — not like curing a sick patient; more like a chiropractic adjustment. Later I learned that he was crediting me as a co-writer on that song, and we didn’t talk about it directly, but I did send word back: “You don’t have to do that if you don’t want to.” I did contribute something, but it certainly wasn’t that much. But then in the liner notes of that album, Jason surprised me by saying, “Thank you, Dan Wilson, for being a mentor, because you are one.” I was like, “Ohhh, OK, so it’s all in the mix here.”

[The award-winning songwriter and producer] Ross Golan said this great thing that I’m sure other people have said. There was a lot of griping and bitching going on [recently] about songs with lots of credited songwriters — and how that was almost being critiqued as a kind of proof that songwriting is worse than it used to be: “Oh, now you needed 10 songwriters to write that song.” Ross’ point was: If we used the same criteria now as back in the Motown days, then James Jamerson would have gotten songwriting credit on tons of those songs. There were Semisonic songs that started from a drum beat, and Jacob Slichter would get songwriting credit for that. But that wasn’t really done back in the day, so they made it look like one genius wrote the song. And now it’s like, “It’s a group effort.” It doesn’t mean the songs are worse — it just means the standards of credit are changing.

I read in one interview that Liam Gallagher basically forgot about your plans to collaborate, and you wound up writing some songs that morphed into the latest Semisonic EP. How often are you able to repurpose something? Do you have a big briefcase full of songs that you’re showing around, like a traveling salesman?

That’s interesting. I think about [hitmaking songwriter] Diane Warren, who has a sort of famous library of existing songs. Legend has it that, even now, when people want to see if Diane Warren has a song for them, she’ll look through the list and say, “These are the three you must do” — very much like a wizard in a Lord of the Rings movie, looking through some ancient library. I have so many songs, but it rarely occurs to me that one of them is going to suit somebody. I’m much more likely to get together with somebody in the moment and get swept up in conversation, or maybe they have a title or I have a title, or I have a couple lines of melody, and we work from there. It’s seldom that I say, “Let’s look in my briefcase full of songs.” But the world has done that. There was a song I wrote with Johan Carlsson and Ross Golan called “Lovers Never Die,” and it bounced around from person to person. And then quite a while after we wrote it, someone played it for Céline Dion, and she put it on her most recent album. That was not me pitching anything — the business did the pitching almost.

How did the collaboration with Nas come about? That’s such a unique entry in your catalog.

Nas and Nas’ manager contacted me to set up a session. Basically I said, “I’d love a day to just talk about song ideas, and I’d love to have a piano nearby where I could come up with some piano riffs.” I think [they were] also thinking we should get together with Al Shux, the producer. So Nas and I hung out for an afternoon, talking about what’s going on in life currently and what Nas was hoping to accomplish with the next album, and me kinda playing piano off and on. And we recorded some piano bits that I thought of.

The next day, Al Shux came, and we learned that Nas had gone down to Atlanta to take care of some stuff. It was just me and Al working on things. I had to go and couldn’t participate in the last part of the process, so Nas came at the end of the week, and they had an epic 24-hour all-nighter recording and writing session to wrap up the couple ideas we’d started at the beginning of the week. It was very unusual. Sitting and talking about stuff with Nas was fascinating. I’ve admired him for a long time. It was a team effort, really proud to be part of it.

After co-writing Adele’s “Someone Like You,” it feels like your career went to this other place where you were working with bigger artists like Taylor Swift and John Legend. Did more people start reaching out to request you specifically?

It was only the things I would have said yes to anyway, like Taylor Swift or things that were less prominent [that turned out well] — the ones where saying yes was only driven by admiration. It turned out those opportunities that looked smart were always dumb. One of the main things that happened with “Someone Like You” is that, for several years, I had to contend with that thing my filmmaker friend predicted: that I’d be offered a lot of things that would turn out to be unsuited for me.

There’s a lesson in there.

I feel like you can’t really fool music. You can’t really trick music. You only get to do it right. You can’t say, “I’ll make this shit because the kids like it.” I don’t think that ever works. I’m not saying I’ve ever said that or done that, but you can’t even do something slightly like that. Music can tell if you’re faking it.