‘Dark Side’ @ 50: The Unstoppable Influence of Pink Floyd’s Masterpiece

How the LP’s cinematic production and outsize ambition transformed every corner of the pop landscape.

by Ryan Reed

For extensive Floyd curation, visit TIDAL’s new Pink Floyd Experience located on the Rock/Indie page.

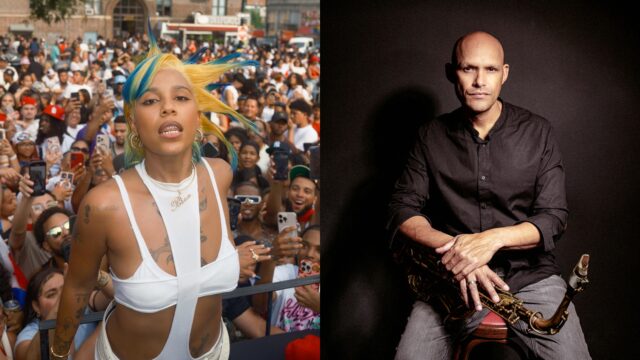

You know you’re living in a post-genre universe when the most impactful Pink Floyd homage of late belongs to … Lil Yachty? After building his career on zoomer-friendly, beat-oriented pop-rap, the artist went full psych-rock on his fifth LP, Let’s Start Here, released in January. “It’s not like I was stepping into a new world — this is music I’ve listened to since I was a baby,” he told Rolling Stone. “[To hear] an album like Dark Side of the Moon and say, ‘OK, I want to go make my version…’ That’s not some easy album to make.”

An understatement, to say the least. But the monumental size of that age-old task hasn’t stopped people from designing their own expansive opus: In the 50 years since its release in March 1973, Dark Side’s influence has been inescapable.

The album has long been an overused, clichéd critical reference point — such an obvious name-drop that most musicians steer clear of it altogether. But the minutiae of these songs — the ultra hi-fi production, the cinematic reprises and sound effects, the loosely connected lyrical themes that nod to the concept album without bowing down to it — are now fixed on our collective mood board of trippiness. At this point, Dark Side is synonymous with the virtues and vices of album-rock ambition.

The record’s fingerprint is so vast you have to trace it into categories. Some artists, including many from the post-rock world, seem to have absorbed Dark Side’s tasteful instrumental balance and distinctive slow-burn dynamics. Take Iceland’s Sigur Rós, who evoke the same grandeur as, say, “Breathe,” on their 2007 track “Í Gær,” rising from swampy Hammond organ and metronomic, Nick Mason-like drumming to volcanic full-band eruptions. Meanwhile, their 1999 epic “Svefn-g-englar,” with its sonar keyboard pings and mountain-sized guitar reverb, is like “Time” from another time; you cling to every cymbal splash and chord change.

And then, of course, there is the production: Few rock albums before or since have sounded so immaculate, so intentional about the shimmer of each note. A young engineer named Alan Parsons, who’d previously assisted on the Beatles’ similarly pioneering Abbey Road, was key to that craftsmanship, helping the band take advantage of EMI’s higher-tech tape machines and layering in experimental flourishes that bloomed further on headphones. Naturally, many albums carrying on that lineage have been guided, at least in part, by production maestros who find clever and innovative pathways to strange sounds — and blur the line between technical crew and group member.

Nigel Godrich has made major records with everyone from Paul McCartney to Red Hot Chili Peppers, and few of them recall Dark Side of the Moon in any tangible way. There’s one major exception. Though he worked with the band earlier, he’s essentially been the sixth member of Radiohead since 1997, the year he and the British art-rockers teamed up to create OK Computer, still one of the most acclaimed albums of all time — and, to many critics, the Dark Side of its era. The parallels are numerous: Both LPs traffic in universal themes (isolation, modern travel, mental illness) and social critique, and they share a sense of front-to-back drama. Everything about the listening experience feels holistic by design, tailored with catch-your-breath interludes and jarring shifts in emotional intensity. Both bands were also dabbling in new textures: Floyd’s sequenced synthesizers and white-noise electronics (“On the Run”), soulful vocal ad-libs (Clare Torry’s virtuoso wailing on “The Great Gig in the Sky”) and interspersed dialogue and effects (heartbeats, laughter); Radiohead’s wild drum processing (the hollowed-out thump of ballad “Climbing Up the Walls,” the trip-hop crunch of “Airbag”) and eerie, discordant orchestrations, as well as the full-blown prog odyssey of “Paranoid Android.”

Like Godrich, producer Dave Fridmann is like a musical cinematographer, helping create vividly painted rooms for songs to exist inside. Also like Godrich, he’s essentially an honorary member of a major rock band, having worked with Oklahoma oddballs the Flaming Lips (almost) consistently since 1990. While all of their collaborations have at least some Floyd flavor, their definitive Dark Side descendant arrived in 1999 with The Soft Bulletin, a symphonic-pop masterpiece that redefined “widescreen” for all alt-rock to follow.

There are specific sonic touchstones throughout the LP. The static electronic pulse that opens “What Is the Light?” might as well be a direct homage to Dark Side’s opening and closing heartbeat effect, and with its somber acoustic piano and ambient noise backdrop, “Sleeping on the Roof” is like “Great Gig in the Sky” minus the blast-off. But the comparison also works on a more abstract, gut-feeling level: These are two albums built for introspection, even at their most euphoric, constructed on big ideas and bigger sounds. (The Flaming Lips are unabashed in their Dark Side love, and reimagined the album in full — with help from Stardeath and White Dwarfs, Henry Rollins and Peaches — in 2009.)

Even though Dark Side isn’t an overt concept album, it evokes that feeling through its sequencing and sonics, and its blockbuster success reinforced the idea that music of outsize aspirations could be worthwhile for everyone — artists, fans and executives alike. Its shadow is certainly omnipresent in realms like prog and prog-metal, where narrative-based double LPs are de rigueur. (Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, who cites his two formative childhood LPs as Dark Side and Donna Summer’s Love to Love You Baby, actually prefers the term “conceptual rock” over “prog.”) But Pink Floyd’s ambition has trickled down through just about every other corner of popular music as well, from industrial rock (Nine Inch Nails) to emo (My Chemical Romance) to hip-hop (Lil Yachty, Kendrick Lamar, Kanye West, Kid Cudi, who has a The Wall-themed tattoo on his right hand). As long as artists continue to crave adventure — and fans maintain the attention span for it — there will always be someone waiting to unlock their Dark Side.