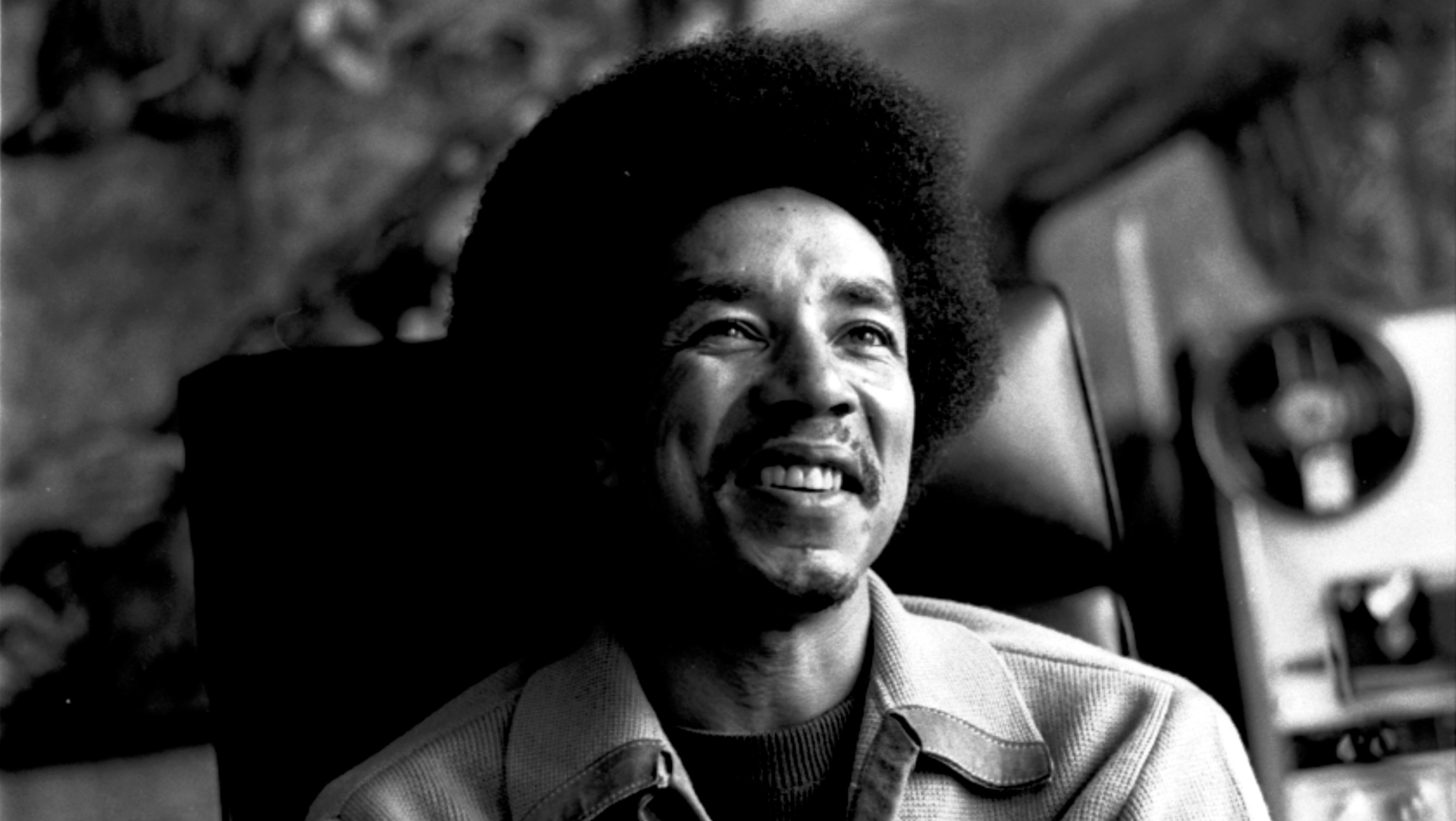

Finding Your Path: Smokey Robinson

The soul icon reflects on his new covers album, not being able to retire, the 50th anniversary of A Quiet Storm and almost giving away “Shop Around.”

by Tony Gervino

Smokey Robinson’s just-released album of mostly cover songs, What the World Needs Now, is quintessential Smokey: trademark silky tenor vocals weaving in and out of the instrumentation, adding new life to songs like the title track, “What a Wonderful World” and “Three Little Birds.” WTWNN is a feel-good record at a time when music fans desperately need one. The major difference between this release and the lion’s share of Smokey’s other work, however, is that, although he personally selected the cover songs, the 85-year-old Detroit native didn’t produce any of the tracks, and only wrote two of them. I asked if it was easy for him to give up control of a finished product bearing his name — something he has not done in his seven-decade career. “I found out it is, definitely,” he responded, laughing.

By any measurable standard, Smokey Robinson has written, sung, produced, engineered and A&R-ed some of popular music’s greatest and most important songs. In addition to his work as chief songwriter and singer for Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, a relationship that began in ’55, Smokey was there for the birth of Motown, working alongside Berry Gordy, while crafting songs for everyone from Marvin Gaye and the Temptations to the Supremes and the Four Tops. During his solo career, he wrote and recorded songs like “Being with You” and “Cruisin’,” which are stitched into the unconscious of anyone who listened to the radio in the ’70s and ’80s. And his ’75 album A Quiet Storm even spawned a radio format of the same name.

In the early ’70s, Smokey, who currently splits his time between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, decided he’d spent enough time living in the cycle of writing, recording and touring and leaned into his second career as a label executive. But, in one of the least surprising developments in music history, he scuttled that plan after only three years and made a triumphant return to continue to burnish his reputation as one of history’s greatest and most influential entertainers.

Below is an edited version of a conversation that took place last week at a New York City recording studio.

TG: As a teenager, you were a songwriter, a producer, a bandleader. Where did you learn those skills?

SR: I think my musical training was from [Motown founder] Berry Gordy. You know, I met him when I was a teenager and, before he started Motown, he was a record producer and a songwriter himself, and he took an interest in me. A year or so later, he started Motown.

TG: You’ve written some of the most memorable songs in the American songbook. Do you have a specific method for writing?

SR: No, there’s no pattern, not for me as a songwriter, anyway. I mean, it could be a melody, it could be some words, it could be whatever tinkling at the piano when something comes to me, you know, but there’s no pattern, it just happens.

TG: Do you enjoy writing songs more for other people or yourself?

SR: I enjoy writing songs, period, man, yeah and I think I do enjoy writing for other people because I enjoy working with other people and trying to do something to contribute to their careers, if possible.

TG: Have you ever demoed a song that you wrote for someone else and decided to keep it?

SR: I think that as far as that goes, I’ve only had two songs really that I demoed with the intention of them being for other people and they ended up being for me. And that was the first million-seller we ever had at Motown, “Shop Around,” which I had written for Barrett Strong. He had a song, “Money (That’s What I Want).” You know, [sings] “The best things in life are free.” And so, Berry wanted me to do an album for him and I wrote the song “Shop Around,” thinking, you know, what do you do with money, you shop and so … [laughs] I thought it was a great song for him and I played it for Berry, and Berry said, “No, I want you to sing it,” and he finally convinced me, thank God.

TG: Is it harder to produce a song you’ve written that you’re also performing on, or is it more difficult to have somebody from the outside give you their opinion?

SR: I don’t think I’ve ever done a song just where I wasn’t accepting any opinions or anything like that. And especially being in Motown because we had Monday morning meetings where we critiqued each other’s music before it came out. Only the creative people were allowed in those meetings, the songwriters and the producers, and we’d critique each other's music and, you know, and try to make it the best it could be. I think that’s one of the reasons we were so successful, because even though we were competitors, we were in it for each other.

TG: You’re on the same team, and so a rising tide …

SR: Exactly, yeah.

TG: Do you have a favorite song that you’ve written?

SR: No, man, I could not possibly tell you what my favorite song is, and probably if I could tell you my favorite song, it would be a song that I had absolutely nothing to do with. I only know my favorite album of all time, and that’s What’s Going On by Marvin Gaye. It’s my favorite because I think it’s a prophecy. If you listen to it today, it’s more poignant than it was when it came out.

TG: Do you remember the first time you heard it?

SR: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I heard it while Marvin was writing it, because he and I were together almost every day. It was either at his house or the Motown building. He’d be writing and I’d listen and say, “Man, this is great.” He told me, “Smoke, I’m not writing this. God is writing this.” He said, “I’m just sitting here. I’m a catalyst.” And I believe him, because you listen to it and hear what he’s saying and it still hits today.

TG: The things you’ve seen and the things you’ve done have made musical history.

SR: I’ve been lucky.

TG: Switching gears, it’s just the 50th anniversary of A Quiet Storm, which was your comeback album after your early ’70s retirement. The reviews were positive but more importantly, it defined a radio format as well, also called “quiet storm.” Did you know that at the time?

SR: Well, no, that was surprising to me also, because A Quiet Storm was just the idea that I had for my debut back into show business. I had been retired for about 3 years or so, and I always felt like I was a quiet singer, and I said to myself, “OK, I’m gonna go back and I’m gonna take show business by storm.” So it was a surprise. But a good surprise.

TG: So when you took three years off and you weren’t recording or performing, it was to focus on your label duties?

SR: Well, yeah, I had no intentions of ever being a recording artist again. You know, when I retired, I retired. I thought to myself, “I’m just gonna go to my office every day and do that and blah, blah, blah.” And that was my plan, but after about three years or so I was climbing the walls, man.

TG: As someone who works in an office, my plan would be the exact opposite. [laughs]

SR: Well, see, but I’ve been on the road all my life, man. I’ve been on the road since I was 16 years old, you know, so I was tired of that. Well … I thought I was anyway, and so I retired from the Miracles and I would go to the office every day, and after three years, man, it was just too much.

TG: With the Miracles, even though you were so young, you were really running everything. You’re managing egos, writing, singing, you’re running music production, you’re touring, performing. That must have been, in and of itself, exhausting. Do you think you would have enjoyed it more if you hadn’t had to handle all of those aspects of it?

SR: No, man, because there’s nothing, even the negativity, that I would change. Because it’s life lessons. Everything I’ve done has taught me something, negative or positive, I’ve tried to learn something. But also, especially when you’re a kid like that, you’re not thinking about the perils of it. You’re not thinking about, you know, “Well, this is hard,” or “I just got too much work.” You’re just loving what you’re doing because it’s your impossible dream and it’s coming true, so you’re not thinking about the negativities that come along with it.

TG: Do you still enjoy playing live?

SR: Hey, man, that’s why I still do it. I can’t find anything that replaces it for me. I don’t get joy like I get on stage being with people and having a good time with people anywhere else in my life. So yeah, I still do it for that reason.

TG: What would your advice be to someone at the beginning of their career?

SR: My first advice to young people? Get control of yourself and your ego. Know that you didn’t start this, and you’re not gonna finish it. I’ve seen thousands of people come through show business, and I’m not exaggerating that number. They come through and they get a hit record and a little notoriety, and they start to believe that the world cannot possibly survive without them now because it’s aware of them. That’s a bad mistake. Like I said, it started way, way, way back before your great-great-great-great-grandmother was born, and it’s gonna be going on when your great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren are there. So you didn’t start it and you’re not gonna finish it, but you’re gonna be a part of it, and you’d better appreciate that and you’d better understand that. And know that you have to carry yourself in that manner because the world don’t need you and show business is a very, very fickle life and a very fickle business.

TG: You clearly still love your job.

SR: I do. That’s because I’ve never lost a spark. I still have that same spark and I have that same feeling every night. You know, it’s a joy for me, you know, I’m very, very blessed to have a life that I love like that and earn a living at it.

TG: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received from anyone? Not just in music, but words to live by?

SR: My mom passed away when I was 10 years old, but my mom always spoke to me in parables, so when she would tell me something she would never tell me the meaning of what she said. So one day I’m crying about, you know, some childhood stuff. I’m probably 6 or 7 years old, and my mom, whatever was going on, says to me, “From the day that you’re born until you ride in the hearse, there’s nothing so bad that it couldn’t be worse.” Now, she didn’t tell me what she meant. I had to figure it out for myself, so that’s how I feel.

TG: Your voice is singular within the Motown universe. Like, there are a lot of the Motown voices, David Ruffin being the best example, with powerful, emotional tenors and yours is more of a delicate instrument, which complements the music without overshadowing it. Who were your favorite vocalists?

SR: In high school, I sang second soprano in the choir, but all the guys that I really, like, idolized as singers were all tenors. They all had high voices, though — Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, Frankie Lymon and so on. So I guess I tried to pattern myself after them as a kid growing up, and my voice has changed a couple of times. That’s the perils of being a guy and, and being in show business when you’re a teenager — you don’t really realize that your voice is gonna change. That was a rough period. [laughs]

TG: If you didn’t create music, what do you think your career path would have been?

SR: I don’t know, but I’ve always had a job, man, from the time I was 10 years old, because my older sister came back to raise me after my mom passed and my older sister ended up having 10 kids, so there were 11 of us. So when I graduated from high school in June, I was working for Western Union and I was delivering telegrams on a bicycle. And rather than me going to college in September, I decided to [stay at the job] until January to save money for books and clothes. In August, by chance, I happened to meet Berry Gordy at an audition. And by December — and this was pre-Motown — he’d recorded the Miracles. So I’m sitting in college in February, and I had a transistor radio to my ear and I heard the record and I … went … apeshit. And that was when I stopped with college and went out on the road. But I was a teenager and I’d been on the road since that time, you know what I mean? And so when I retired, I thought, “Hey, I’ve had enough of this,” the Miracles had done everything that a group could possibly do, and we had done it 2 or 3 times. We’ve been all over the world, so, you know, I was tired. So I, I said, you know, I’m gonna look forward to just going to the office every day doing that, and that was true for a while, but after that you’re in an office and people are complaining about something and you’re like, “What am I doing here? I could be out on the road.”