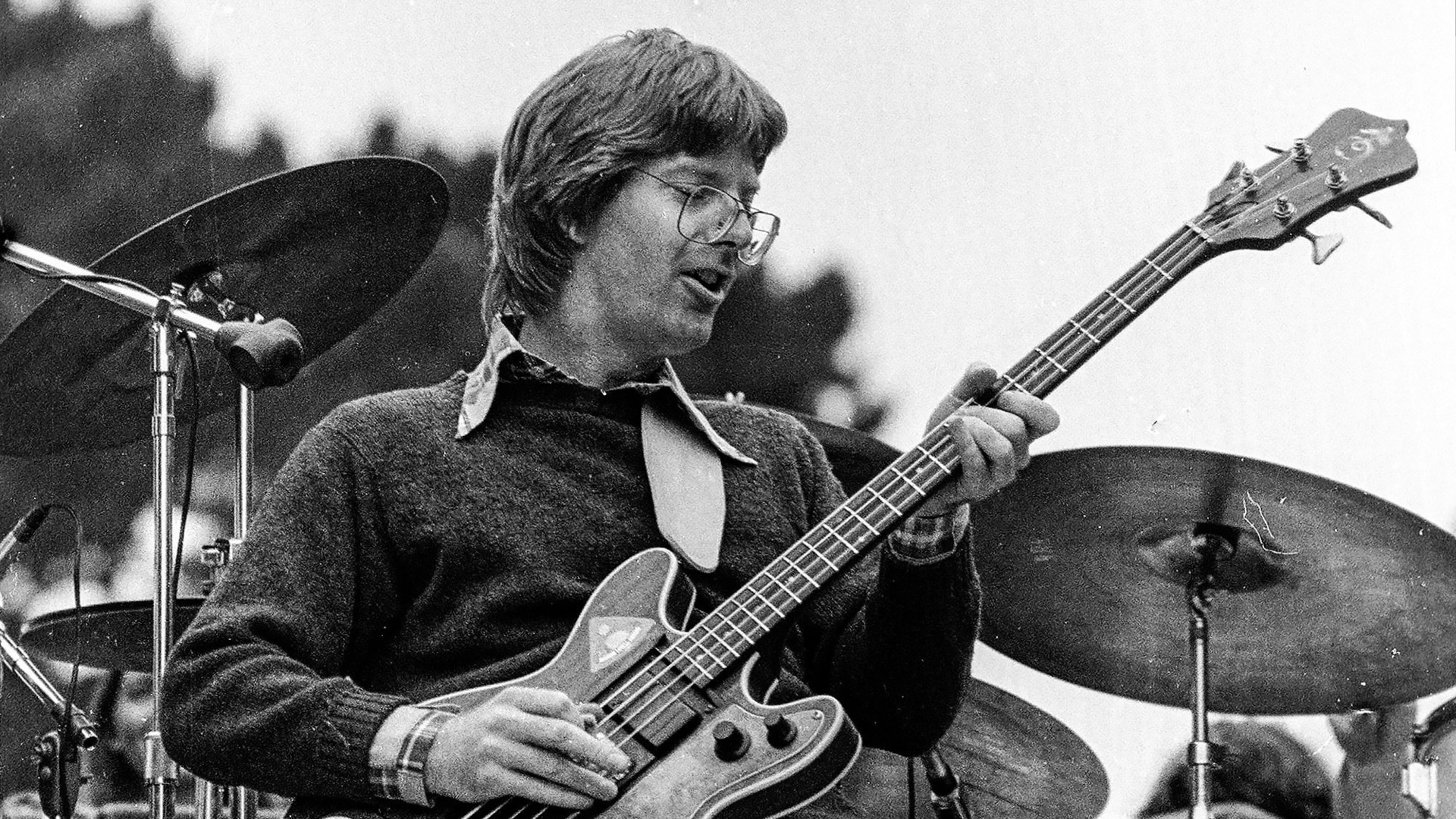

Phil Lesh: Professor of Improvisation

The Grateful Dead bassist, who died last month at 84, mentored younger players and led one of the most influential jam bands of the early 2000s.

by TIDAL

By journalist, biographer and musician Alan Paul. All quotes were told to Paul for Guitar World pieces in 2000 and 2002.

Bassist Phil Lesh’s death on October 25 was a jolt to the Grateful Dead community and the larger jam band universe. Lesh, who was 84, was one of the most active performers of the last quarter century. Since his Phil Lesh and Friends started performing regularly in 1998, until his final performance, on July 21, Lesh was a stalwart of top-notch improvisational music, playing the Grateful Dead (and related) canon with adventurousness and joy. And he was joined, over the years, by a large cast of musicians.

It was striking in the days after Lesh’s death how many musicians shared on social media that the bassist changed their life, or was their greatest influence. By playing with rotating musicians for the last 25-plus years, Phil ran a PhD program in the Dead and improv, seeding hundreds of newly minted Doctors of Music with an approach and integrity that will continue to ripple for decades to come. Two generations of younger musicians passed through Phil’s bands and have taken the wisdom and knowledge back to their own performances.

Lesh joined the Dead in 1965, the year the band started, when they were still called the Warlocks. He was enlisted by Jerry Garcia, a casual friend, to become their bassist, even though he had never touched a bass. On the surface, it made very little sense, but the ever-perceptive guitarist saw Lesh’s potential. A classically trained trumpeter and composer, Lesh was a brilliant musician with a wide-open mind. He embraced the avant-garde and had a newfound interest in rock and roll thanks to Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Given his freewheeling background, it was no surprise when he quickly discarded any preconceived notion of the bass’ role.

“I’ve always wanted to avoid exact repetition and that put me against the grain of rock bass, which at the time was tied to the root of the chord or followed the bass drum,” Lesh said. “It’s okay to repeat an idea once, but then I like to do something different, like displacing the rhythm by half a beat or not playing a root in a melodic section.”

His style, he added, “really evolves out of the more melodic function of the bass line in classical music, which is often played by a cello or a bassoon.” Lesh’s interest in modern experimental music also exerted a huge influence on a group that began as a folk-y jug band. The Dead were a pretty standard dance-rock band of the day when they first went electric, playing blues patterned after the Rolling Stones as well as adapting some old-timey tunes.

Lesh was, in many ways, the least likely member of the Grateful Dead to carry on the band’s musical legacy following Garcia’s 1995 death. It initially led him to stop performing — he spent two years working on a classical score based on Dead compositions, and avoiding rock music. But an impromptu club jam with some local Bay Area musicians illuminated the impact his former band’s music had had on so many.

He then faced a life-or-death health crisis. Suffering from hepatitis C, he was on his deathbed before being saved by a liver transplant in December 1998, receiving an organ from a young man named Cody. He talked about Cody at every subsequent show, urging his crowd to become organ donors, and readily admitted that his liver transplant and his “second life” radically reshaped an already passionate relationship with music.

“Every note is more precious now,” Lesh told me in 2000. “Every moment is more precious.”

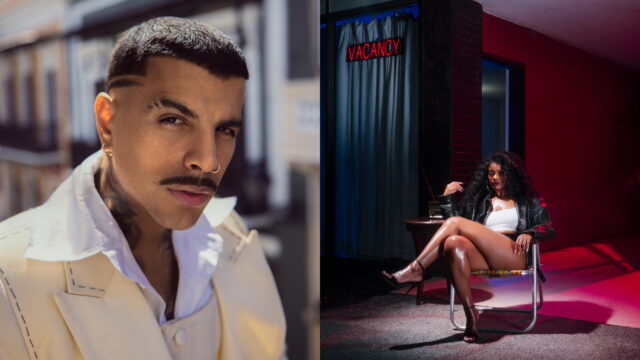

Four months after his transplant, Lesh celebrated his renewed health by leading a band featuring Phish’s Trey Anastasio and Page McConnell in a series of concerts, exploring the Dead’s catalog. The joy he found in these performances, and amongst the fans, led him to continue the ongoing, morphing Phil and Friends band. By 2000, he had found a group that clicked so thoroughly that he stuck with them for several years: guitarists Jimmy Herring and Warren Haynes, drummer John Molo and keyboardist Rob Barraco. This group, known as the Phil Lesh Quintet or “the Q,” toured extensively, and released a strong studio album, There and Back Again, in 2002.

“There was no master plan for the band,” Lesh said. “Initially, each event was a one-off thing and the musical chairs aspect was really at the forefront for the first three years.” The very first rehearsal with Haynes, Lesh said, “was so explosive that I didn’t want to rotate any more. I knew it couldn’t get any better. It also was a lot of work to constantly teach new players this repertoire, which was rapidly expanding.”

Haynes and Herring are friends of mine and I was fortunate to attend many Q shows over the years and spend a fair amount of time with the group offstage as well. Several of these performances are amongst the greatest, most moving shows I’ve ever attended. Many Deadheads refer to the Phil Lesh Quintet as “the best post-Jerry Dead band,” but that is actually faint praise. They were one of the greatest live acts of their era.

“Phil faced down death and came out the other side and decided to do exactly what he wants with no compromise,” says Haynes. “That meant a band which maintained the Dead’s improvisational quality while also being more structured. Phil rehearsed more in the first six months with this band than he did in the last 10 or 15 years with the Dead.”

In 2000, I arranged for Anastasio to interview Lesh and it became a wide-ranging conversation about the power of music, the perils of stardom and much more. It was difficult to arrange, but Anastasio was committed to the idea from the beginning, thrilled by the opportunity to pick the brain of one of his musical heroes.

“I welcome any opportunity to sit and talk with Phil, which was one of my favorite things about playing with him,” Anastasio said then. “Anyone who really cares about music can learn a lot from this man.”