Raíces Sonoras: How Artists Are Reclaiming Heritage Through Sound

Bad Bunny, Rauw Alejandro and Karol G are reaching into the past to meet a politically charged present.

by Celia San Miguel

Bad Bunny’s historic, 31-date “No Me Quiero Ir De Aquí” residency in Puerto Rico concluded on September 20, precisely eight years after Hurricane Maria devastated the island. Choosing to conclude the concert series on this date could hardly be deemed coincidental — after all, just one year earlier, Bad Bunny released the ominous, anxiety-riddled “Una Velita,” featuring the woeful strings of a Puerto Rican cuatro guitar over increasingly furious bomba-inspired rhythms. In “Una Velita,” Bad Bunny describes the collective trauma experienced by islanders in the aftermath of Maria — the pain they suffered at the hands of apathetic federal politicians (President Trump’s government withheld an estimated $20 billion in hurricane relief, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Inspector General) and incompetent local officials (some of whom hoarded supplies in warehouses for more than two years). “Una Velita,” then, is a rallying call, a warning that Puerto Ricans will never forget the nearly 3,000 lives that were needlessly lost due to government neglect. And it’s a reminder that it’s up to the community to save itself.

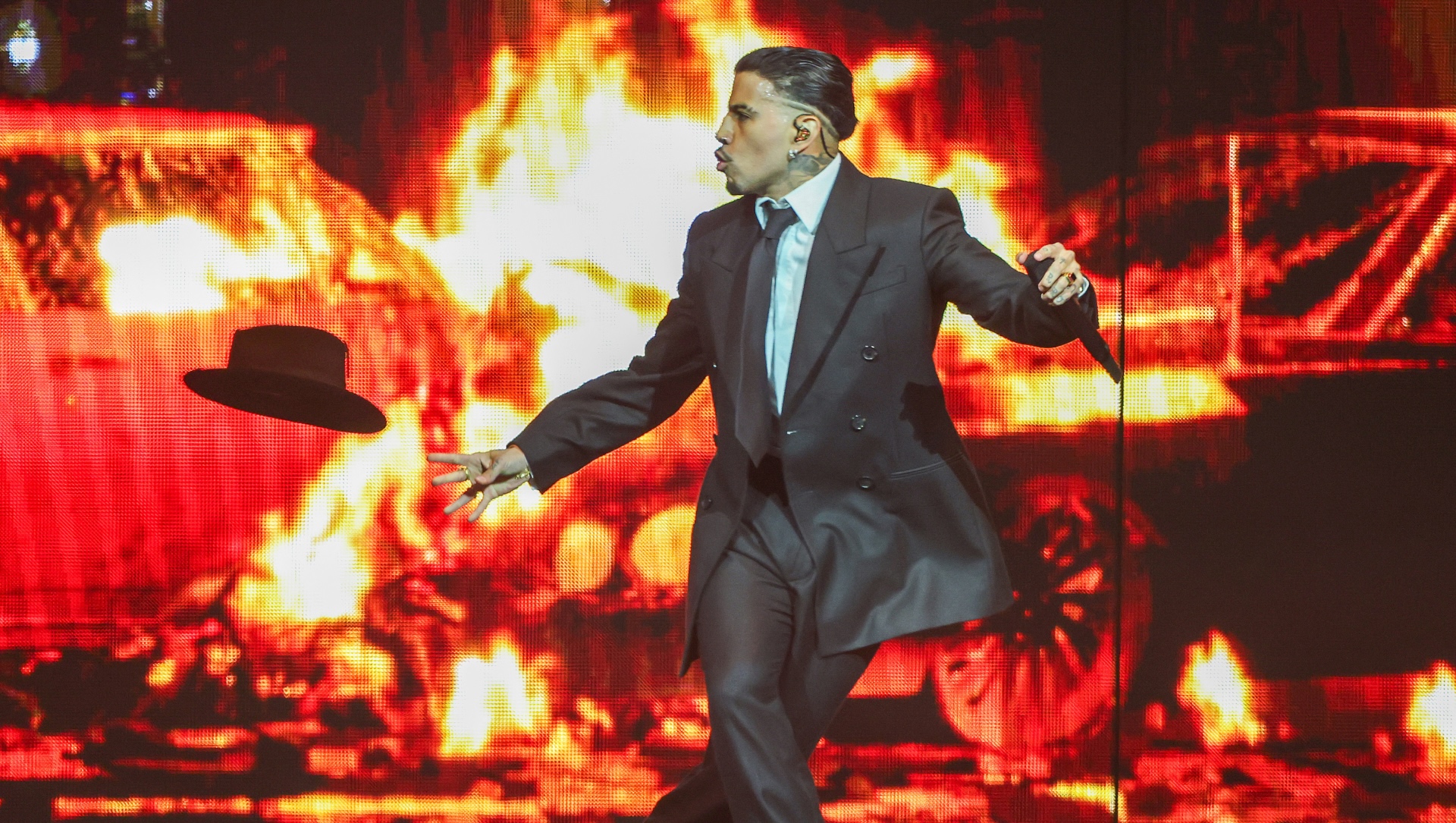

If “Una Velita” sparked a conversation about the need for Puerto Rico to enjoy political and economic autonomy, Bad Bunny’s residency — and the 2025 album that inspired it, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS — intensified the flame, igniting a sense of cultural pride among Puerto Ricans as fiery and vibrant as the flowers of the iconic Flamboyán tree (itself a crucial component of the concert’s set design).

Bad Bunny’s mission to elevate and preserve Puerto Rican culture and history involves centering the sounds of the island — not just salsa and reggaetón but also the traditional sounds of bomba and plena. In fact, during the show’s theatrical opening, Afro Puerto Rican percussionist and bandleader Julito Gastón emerges on stage, treading along the campo landscape, lamenting the loss of his drums and asking audiences if they’ve seen his beloved instruments. Upon locating his drums, Gastón drops to his knees in gratitude, remarking that everything has been taken from him, that all he has left is his tambor buleador. He explains that the drums are his paño de lágrimas (a cloth to wipe his tears), a reflection of his being, and that he’ll protect them at all costs. Only once his hands begin to strike the drum does the show truly begin: music fills the coliseum and Bad Bunny emerges to interpret his most recent single, “ALAMBRE PúA,” a bomba-steeped track featuring heavy bass and entrancing synths. The message is clear: all Puerto Rican music begins with bomba, a musical form created over 400 years ago by enslaved Africans on the island’s sugar plantations as a means of resistance and self-expression.

Traditionally structured as a call-and-response genre in which drummers and dancers use rhythms and movements to communicate, bomba has survived through oral tradition, with the music being passed down from one family to the next. During the aftermath of Hurricane Maria and the 2019 protests that led to the resignation of then-Governor Ricardo “Ricky” Roselló, islanders turned to bomba to express their frustration, transforming communal expressions of music and dance into forms of political demonstration, while also creating joy through communal resistance.

Dubbed “the people’s newspaper,” plena is another traditional Puerto Rican music genre that plays a prominent role in DTMF, thanks to the ebullient “CAFé CON RON,” featuring Los Pleneros de la Cresta. Born in Ponce’s working class neighborhoods in the late 19th century, plena involved lyrics about the challenges of everyday life, and the injustices incurred by poor and marginalized communities — all sung over a rhythm created primarily with panderos (hand drums). Like bomba, plena is known as freedom music. As such, it’s an integral part of an album that celebrates Puerto Rico’s beauty and the resilient spirit of its people while also lamenting the territory’s current state as a modern-day colony, and warning about the displacement caused by gentrification (the latter resulting from tax cuts for wealthy investors and tech entrepreneurs stateside).

“No Me Quiero Ir De Aquí” wasn’t just the name of Bad Bunny’s residency — it was and is the sentiment of all the islanders who have remained on their native soil despite endless hardships like constant power outages, low wages, rampant inflation and a clean drinking water crisis. It’s also the sentiment that expats have expressed while tearfully heading to places like Florida and New York in search of financial stability, better education systems for their kids and reliable municipal and state government services. The fight to remain on the island — and the melancholy experienced by those displaced— are prescient issues explored in “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii,” a woeful ballad that incorporates the Puerto Rican cuatro and güiro, both key instruments in la música jíbara.

The sentiments expressed in “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii” echo those of the classic, heartbreaking ballad “En Mi Viejo San Juan,” about an expat longing to return to his beloved homeland but finding himself unable to do so. Penned by Noel Estrada in 1943 and first recorded by El Trio Vegabajeño in 1946, “En Mi Viejo San Juan” has become part of the musical canon for the Puerto Rican diaspora. Unlike “En Mi Viejo San Juan,” however, “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii” directly addresses the issues causing the mass exodus of Puerto Ricans, calling out political corruption within the island and lambasting the foreign real estate developers attempting to privatize Puerto Rico’s public beaches, as well as the economic forces expelling people from their family homes. The música típica instruments in the song’s composition magnify its emotional power, so that it feels like the anguished cry of a jíbaro (a term originally reserved for farmers in Puerto Rico’s countryside that has now become synonymous with Puerto Rican pride and identity).

In DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, then, Bad Bunny uses the sounds of Puerto Rico — bomba, plena, salsa and reggaetón — to inspire cultural pride and mobilize la resistencia. His desire for an independent Puerto Rico is most evident in the salsa number “LA MuDANZA,” in which he asks that he be buried with the Puerto Rican flag with the azul clarito (light blue) triangle, a reference to a version of the flag created in New York City in 1895 by the Puerto Rican section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, which advocated for the island’s independence from Spain. In 1898, when the U.S. military occupied Puerto Rico, the flag became a symbol of opposition to the new colonial rule. It became so synonymous with the pro-independence movement in the island that, in an effort to squash any potential uprisings, Puerto Rico’s U.S.- appointed legislature passed La Ley de la Mordaza (“The Gag Law”) in 1948, making displaying the flag an offense punishable by 10 years in prison. In the song, Bad Bunny explicitly references this history of persecuting freedom fighters, singing, “Aquí mataron gente por sacar la bandera / Por eso es que ahora yo la llevo a donde quiera” (“Here, people were killed for raising the flag / That’s why I carry it everywhere”). Also in the song, Benito requests that one of his songs be played when they return Hostos to his homeland — a reference to the 19th century educator and independence advocate Eugenio María de Hostos, who was buried in the Dominican Republic and famously requested that his remains be moved to his native Puerto Rico only once the island had attained independence.

DTMF is indisputably Bad Bunny’s most political album — and the incorporation of ancestral sounds is a key component of how sentiments of pride and resistance are conveyed in the album.

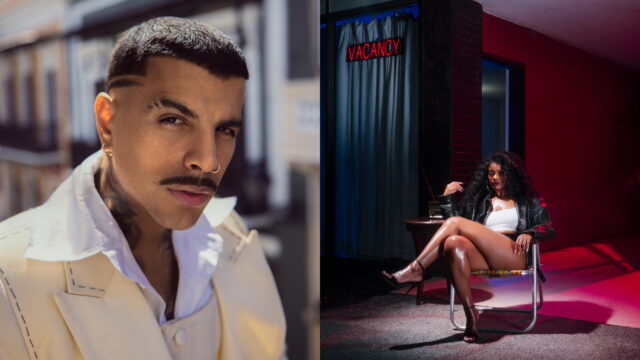

But Bad Bunny isn’t the only Puerto Rican artist finding inspiration in salsa and bomba. Rauw Alejandro offered up a cover of Frankie Ruiz’s “Tú Con Él” on 2024’s Cosa Nuestra, an album heavily inspired by the salsa scene in 1970s New York City. Rauw’s new album, Cosa Nuestra: Capítulo 0, serves as a prequel to his 2024 effort and, fittingly, explores older ancestral sounds – chiefly bomba. The tender “Carita Linda” fuses urban beats with a traditional bomba yubá rhythm, while the darkly sensuous “GuabanSexxx” incorporates a bomba holandés rhythm to create a sense of urgency and danger. Inspired by the Taíno goddess of chaos and natural destruction Guabancex, “GuabanSexxx” warns of a looming tropical storm as embodied by a woman Rauw is powerless to resist —despite knowing it will end in ruination.

While the lyrical content of Rauw’s project isn’t as overtly political as that found in Bad Bunny’s DTMF, his exploration and exaltation of ancestral, resistance-born musical forms like bomba should be construed as a political statement, a way of honoring and affirming the African ancestry that’s often overlooked in discussions of Puerto Rican heritage and culture.

Like Bad Bunny and Rauw, Karol G found herself looking to the past for inspiration when recording her latest album, Tropicoqueta — specifically, to the music that formed the soundtrack of her childhood and sparked her desire to sing. She recalled a mosaic of sounds ranging from Colombian vallenato to Mexican rancheras, old-school reggaetón and ’80s and ’90s pop. Elements of all these influences can be found in Karol’s genre-hopping, 20-track album. She flirts with techno merengue in the coquettish “Papasito,” which was inspired by Los Melódicos, a Venezuelan tropical music outfit founded in the late ’50s. She imagines soul-crushing heartbreak in the vallenato “No Puedo Vivir Sin Él,”counsels a friend in a toxic relationship in the breezy bachata “Amiga Mía” (featuring fellow Colombian Greeicy) and reimagines George Michael’s “Careless Whisper” as a cumbia villera in “Cuando Me Muera Te Olvido.”

With Tropicoqueta, Karol G takes us on a musical journey that incorporates genres from her native Colombia as well as Mexico, Venezuela, Chile, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic and Brazil, approaching every ancestral sound with respect while lending it a modern sensibility. By returning to her roots and immersing herself in the rich musical traditions of Latin America, Karol G created an album that proudly celebrates Latinx identity. During a time when Latinos in the U.S. are facing increased discrimination and persecution, this unapologetic and exuberant celebration of identity constitutes a powerful statement, reminding us that joy is also an act of resistance.

On February 8, 2026, Bad Bunny will bring joy to one of the world’s biggest sporting events, headlining the Super Bowl LX halftime show. It will be the first time a Latinx artist with an all-Spanish discography takes the stage —which feels momentous in and of itself, but particularly so given the current political climate in the U.S. We’re living in a dystopian era, with oftentimes masked and unidentified ICE agents terrorizing Latinx communities and detaining civilians simply for speaking Spanish or “looking” Latinx (a practice that constitutes racial profiling and, alarmingly, has been upheld by the Supreme Court). For many Latinxs, it seems like our very right to exist is under attack. In this highly charged political atmosphere, it feels monumental for Bad Bunny to take center stage at the Super Bowl and perform all-Spanish songs, many of which are steeped in ancestral Puerto Rican sounds and are rife with sociopolitical meaning. By simply performing his songs his way, in his chosen Spanish language, Bad Bunny will be combatting this administration’s efforts to vilify and erase the Latinx community. And he’ll do it with sazón, batería y reggaetón.